How should LPs think about VC fund size?

Venture is not a monolith any longer, and nuance is required to assess fit

What does fund size mean in venture today?

A few weeks ago, I shared some thoughts on Twitter and LinkedIn about the evolution of venture capital and how LPs should think about deploying capital in today's market. The venture capital landscape has fundamentally changed, and it's time our frameworks caught up.

Twenty years ago, venture capital was relatively uniform. Most firms followed similar strategies, wrote similar check sizes, and built portfolios in roughly the same way. This uniformity made sense—technology was still early in transforming the world, and the annual venture capital deployed was a fraction of what it is today.

But the industry has transformed dramatically. The rise of institutional seed funds, the emergence of mega-platforms, and the sheer scale of the industry have turned venture capital into a collection of distinct strategies. Yet many LPs still use a monolithic lens to assess venture capital, which results in the ongoing comparison of "large vs. small" VC funds, which misses the point—these aren't just different fund sizes; they're fundamentally different economic products with unique risk-return profiles and business models.

Each can have a place in an LP portfolio, dependent on risk/return tolerance, capital base, time, access, etc.

To analyze these segments effectively, we can categorize venture funds into distinct size tiers that reflect their different business models:

Small-Cap Funds (<$250MM):

These funds represent most closely the traditional venture model, with their sizes lending toward focusing on seed and early Series A (primarily follow-ons) investments.

Mid-Cap Funds ($250MM-$1B):

Since this is a fairly broad range, I wanted to segment it further by type for this analysis.

Smaller-Mid Cap ($250MM-$499MM): These funds often maintain significant early-stage exposure while gaining the ability to participate meaningfully in follow-on rounds (exposure is generally seed-Series B).

Larger-Mid Cap ($500MM-$999MM): At this scale, funds begin showing characteristics of large-cap funds. In this category there have emerged high quality specialist brands (fintech, enterprise, consumer, deep-tech).

Large-Cap Funds ($1B+): These funds typically can be raised only by strong brands, and the fund size lends to investing across the stage spectrum, and seed investing is normally for optionality. Initial core checks are typically done at the A or B rounds, with exposure often going through Series C/D.

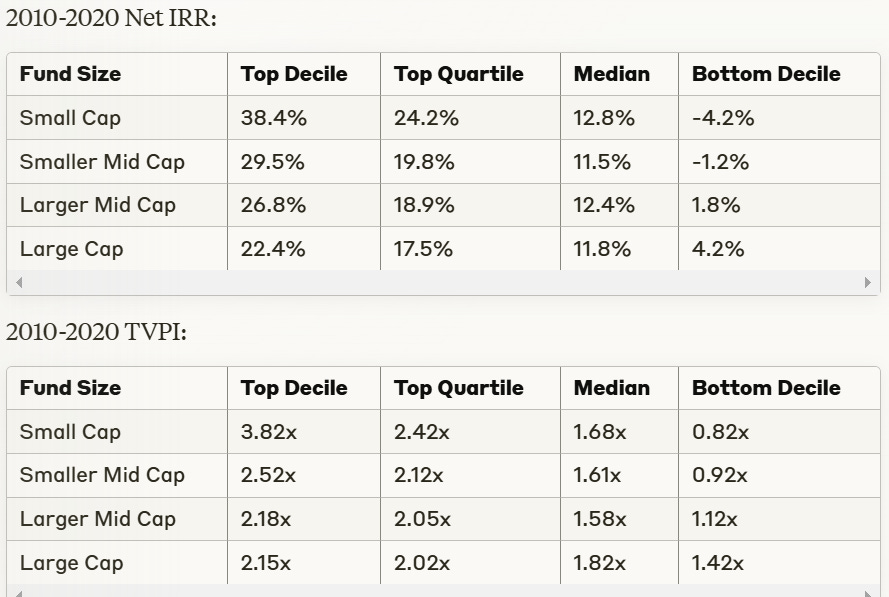

To understand how fund size shapes strategy and returns, I analyzed historical fund performance data from PitchBook across two distinct market cycles: 2000-2010 (post-bubble through financial crisis) and 2010-2020 (post-GFC and ZIRP period). The analysis used simple weighted averages for returns.

*It's important to caveat that returns for funds later in the 2010-2020 cohort may still be too early to entirely rely on.

Small-Cap Funds (<$250MM):

The data shows small-cap funds maintain the closest resemblance to traditional venture investing. The return profile demonstrates the potential for significant outperformance and increased downside risk.

Typical Characteristics:

Portfolio Construction: Typically 25-35 companies, though some managers pursue broader portfolios of 50-100+ companies at pre-seed/seed stages, given limited visibility on eventual winners

Stage Focus: Heavy concentration in Seed- Series A, often deploying 50-100% of capital at seed.

Investment Approach: More likely to pursue non-consensus investments or focus on specialized sectors

Mid-Cap Funds ($250MM-$1B):

Smaller-Mid Cap ($250MM-$499MM):

Typical Characteristics:

Initial core checks at Series Seed and A

Critical focus on ownership

Will follow on in a select group of companies through Series B

25-35 Companies

Larger-Mid Cap ($500MM-$999MM):

Typical Characteristics:

Initial core checks at Series A and Series B

Critical focus on ownership (15-20% minimum for initial check)

Will follow-on in a select group of companies through multiple rounds, often to Series C.

25-35 Companies

Large-Cap Funds ($1B+):

Typical Characteristics:

Full lifecycle investing from Seed to late-stage growth

Critical focus on ownership concentration

Can invest in consensus and be relatively price-insensitive on initial checks to win "best" deals (hot sectors, companies with momentum, or tangibly strong teams/founders)

Brand and reputation as prerequisites

A limited number of firms can operate effectively at this scale.

The Assessment of Fund Size in Portfolio Construction

Small Cap Venture:

Highest return potential with corresponding volatility.

Manager selection is crucial given the wide outcome dispersion.

Best suited for maximum return-seeking portfolios (if manager selection can be done consistently well).

Mid-Cap Funds:

Balanced risk-return profiles.

Progressive compression of returns with scale.

Improved downside protection from small cap, but higher return potential than large-cap.

Large-Cap Platforms:

Most consistent return patterns, with reduced upside/downside.

Strongest downside protection.

Ideal for reliable, scaled venture exposure.

Rethinking Venture Capital Allocation

The evolution of venture capital mirrors that of other private market segments. Just as institutional investors wouldn't compare a large buyout fund to a small-cap niche specialist in private equity, we need to move beyond simplistic "large versus small" comparisons in venture capital.

The data shows that each segment can serve a distinct purpose in portfolio construction, with its risk-return profile and operational requirements.

Small-cap funds offer the potential for exceptional returns but demand both high-risk tolerance and exceptional manager selection capabilities. Mid-cap funds provide a balance of upside potential and portfolio construction flexibility, while large platforms deliver more predictable outcomes with stronger downside protection.

But the choice between these strategies isn't about which is "better" – it's about alignment with objectives, capabilities, and constraints. LPs need to consider several key factors when determining their venture strategy:

Portfolio Construction Considerations:

Return Objectives and Risk Tolerance: Different investors have varying return targets, risk tolerances, and liquidity needs. Understanding these variables should drive portfolio mix (recognizing that portfolios often contain multiple fund types).

Scale of Capital Deployment: The amount of capital you need to deploy significantly influences what practical segments to focus on. Small-cap funds might offer higher potential returns, but deploying $500MM across 20-25 small-cap funds ($15-20MM checks) requires significant operational resources. Conversely, deploying the same amount across 4-5 large platforms ($100MM checks) is more manageable but with a different return/risk profile.

Existing Private Market Exposures: Your current portfolio composition matters. If you already have significant growth equity exposure, a small-cap venture might provide better diversification. Similarly, if you have concentrated early-stage exposure, large-cap platforms might help balance the portfolio by introducing more growth exposure (if risk reduction through balance is a consideration).

Liquidity Requirements and Time Horizons: Different fund sizes typically have different paths to liquidity. Small-cap funds historically have had longer exit timelines given the seed/A exposure. At the same time, larger platforms provide more balance, given that follow-ons done at larger platforms may extend to C/D+ rounds, which have shorter times from investment to exit.

Capabilities needed:

Manager Selection and Due Diligence Resources: The resources required for due diligence vary significantly by segment. Building a successful portfolio of small-cap funds requires significant resources to meet managers (I think to invest in 5 managers per year, investors should be meeting 200-300 managers) along with a deep evaluation of individual managers on whether they have a definable edge when it comes to sourcing, picking, winning, etc. This is necessary to avoid getting small-cap beta returns where investors are not likely to get compensated for the additional risk versus larger funds.

Access: Top performers in each segment have different accessibility challenges. Premier small-cap funds often have small fund sizes and strong existing LP bases, requiring proactive relationship building and sector expertise to access. Larger mid-cap and large platforms might be accessible but require larger check sizes and often prefer LPs who can support multiple fund products over long periods of time.

The correct venture strategy might mean focusing on a single segment or building exposure across multiple segments. For example, a family office viewing venture as an asset class focused on maximizing returns (and where they have the time and expertise to select managers) may be better suited to investing primarily in small-cap venture funds. A pension fund might prioritize more consistent returns in the mid-teens, making large-cap platforms more appropriate.

The key is intentionality – understanding that fund size fundamentally shapes the offered product and choosing strategies that align with objectives. Success in venture capital investing is not about trend chasing or making broad generalizations about fund size. It's about assessing goals, understanding constraints, and aligning a venture portfolio accordingly.

Great post! It made me realize that LP strategically selects not only the GP but also the fund sizes to effectively manage their risk. Thanks :)

Looking backwards this is good work. However, the research shows there is a '3rd way' which combines the best of both; $500MM to$1B can be depoloyed and deliver compelling DPI & IRR, with more confidence and repeatability. See 'Process Alpha: How to Construct and Manage Optimized Venture Portfolios' - https://bit.ly/3UoRYDF & 'The Impact of Optimized Venture Portfolio Construction - Optimized DPI & IRR' - https://bit.ly/3Xniz3V. Take the lessons learned from past successes (broad diversification at the seed round, then proper follow on with the emergent winners). This can be done with as little as $50M invested across Seed/A/B, and not dilute the expected returns up to about $1B across all 3 rounds.